By Kathryn Auten

A young woman was reading the Chicago Sun-Times in the lobby of the Chicago Tribune’s editorial office. She was waiting to hand deliver a news release to George Lazarus.

When Lazarus left his office and approached her she put down the paper and handed him the news release. Lazarus then tore the press release to shreds and dropped them on the floor, said Bill Barnhart, co-worker of Lazarus at the Tribune, as he recalled the incident.

“You shouldn’t read the competition,” Lazarus responded.

Lazarus was a native of Worcester, Mass., and in 1954 he graduated with a bachelor of business administration from Clark University. In 1957, he received a master’s degree in journalism from Northwestern University, according to the Tribune.

Before working at the Chicago Tribune, Lazarus worked at the Chicago bureau of The Associated Press until 1959 and then worked as editor at Printer’s Ink magazine. In 1961 he moved to the Chicago Daily News and then moved again eight years later to Chicago Today. Lazarus joined the Tribune in 1972, where he developed one of the first marketing columns in the nation.

While working at the Tribune, Lazarus wrote for Adweek’s Marketing Week and the New York Daily News. In addition, he wrote “Marketing Immunity” in 1998 and was a business commentator.

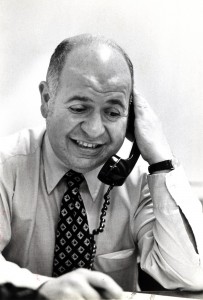

Lazarus established a reputation during the 28 years he worked as a marketing columnist for the Tribune. He was extremely competitive and wanted to be the first to break the news.

Cathy Grisham, currently creative director for Red Circle agency, said that he was the talk at the water cooler and said that you would hear “Have you read Lazarus yet?” said on a normal basis. Grisham has worked as an executive director for Campbell Mithun, creative director for DDB Chicago and associate creative director for FCB Chicago during Lazarus’s tenure.

“You had to read him. He could make you or break you,” said Grisham.

Everyone wanted George to write about them because he had a reputation, but if you broke your news to someone else he wouldn’t carry your story, said Vic Zast, who works on the executive management team for Tru Fragrence.

Zast became acquainted with Lazarus when he worked as senior vice president of marketing for Jim Beam. Zast was frequently mentioned in Lazarus’s column and played tennis with him.

“He had a little bit of a temper,” said William Sluis, a former associate business editor of the Tribune. Sluis was a close friend and Lazarus’s long-time editor even after leaving the Tribune.

A co-worker of Lazarus at the Tribune explained that Lazarus knew he played an important role in both Chicago and New York and that he also didn’t have to play nice to get the information he needed.

Lazarus took a different approach than most reporters. He refused to talk to public relations executives and talked primarily with executives. He developed close and valuable relationships with executives, and in return they would provide him with tips, which is considered an old-school journalism technique.

His competitive nature to be first in breaking the news sometimes intimidated those he would interview for the column.

“I wanted so badly to be in his column that I allowed him to be intimidating,” said Zast.

Zast took a tougher approach with Lazarus than most. Zast said that he became frustrated with Lazarus’s demands, so he turned the tables and told Lazarus that he did not care whether a story ran.

“By doing that I had much greater success in getting stories covered, and ultimately he contacted me,” said Zast.

“George stood his ground, and that’s a good rule for people in journalism,” said Sluis. “Journalists have a tendency to be too nice. We forget that we are doing this job for thousands of people. He had success because he never lost sight of that.”

He was meticulous and had a full-time secretary, unlike other writers, and kept files full of background and source cards and names, said a coworker at the Tribune. “I once told George that I wished someone with his skill was reporting on something more worthwhile,” said the co-worker.

“His profession defined him. It was his greatest pride,” said Zast.

Lazarus attended fundraisers and events in the evenings. The night before he died he attended a black-tie dinner. As he was leaving the newsroom on what would be his last day at work, the entire staff gave him a round of applause, a fitting exit for a legend.

Lazarus was found dead by a train employer on his way in from work Sept. 8, 2000. He was survived by his wife and two children.

“I don’t think anyone who has succeeded George has been as successful,” said Sluis. “There are some writers and journalist that you can’t replace and George was one of them.”

Kathryn Auten is a native of Kannapolis, N.C., and is a business journalism major in the Class of 2015 at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.