By Melvin Backman

There was a time before John Brooks started writing business pieces when the subject was the purview of suits in the C-suite. Then, it became front-page news, and the general public took greater interest in how money is made in America.

John Brooks isn’t the main reason this change took place, but his writings exist deep in its intellectual core.

He wrote for the rarified pages of the New Yorker, spilling ink that was unlikely to stain the hands of a lay worker, but he was still a pioneer, serving as a guide for later business journalists seeking to combine literary flourish with strong analysis.

A member of Princeton University’s Class of 1942, Brooks started his career at Time magazine as a contributing editor after a short stint in the Army during World War II. Two years later, he began writing for the New Yorker and didn’t look back.

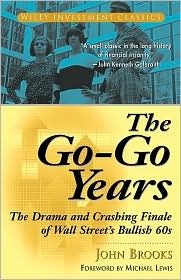

During his time at the prestigious magazine, Brooks brought to life for readers the culture of Wall Street, all of its excesses and deficiencies included. He also published a few books: “The Go-Go Years,” published in 1973, is his most famous, but he also penned 10 other books, including a few novels and a history of Ford Motor Co.’s failed Edsel line.

During his time at the prestigious magazine, Brooks brought to life for readers the culture of Wall Street, all of its excesses and deficiencies included. He also published a few books: “The Go-Go Years,” published in 1973, is his most famous, but he also penned 10 other books, including a few novels and a history of Ford Motor Co.’s failed Edsel line.

Beside the casino nature of American finance, “The Go-Go Years” shed light on the way things were done on the Street during the high-flying 1960s. For instance: women were often almost completely barred from the lunch clubs and restaurants that served high-flying traders taking a break from the market.

His eloquent prose makes the situation plaint: “Even in summer, the air lied heavy, dank and sunless,” excerpted Maggie Mahar in her 2004 Wall Street book, “Bull!” “Pretty women seemed flesh without magic.”

Joe Nocera, the New York Times columnist, recalls picking up Brooks’s writing in the mid-1980s, a few years after he had written his first business article in 1982. By the end of the decade, it was obvious how deeply Brooks had influenced Nocera. A 1988 Esquire article about the Wall Street culture that lead to the “Black Monday” stock market crash a year earlier was titled “The Ga-Ga Years,” a tribute to one of Nocera’s favorite books.

Although he doesn’t believe that every modern financial writer taps a keyboard with Brooks’ prose ringing in her ears, Nocera says that Brooks brought panache to a subject that had previously seemed so staid.

“We now live in an era where business has become a standard subject for reporting,” he said, noting that Brooks stood out to him early in his journalism career.

Eventually, business news would sneak out of office buildings like a young employee on a summer Friday and into the business sections of metro newspapers. Nocera denied that Brooks was responsible for this.

“That would have happened with or without John Brooks,” he said.

Still, the man was a pioneer, boldly writing where few had dragged a quill.

“He was the very, very rare writer of his time who was writing serious articles for a non-business publication and a non-business audience,” Nocera said.

Outside of the newsroom, Brooks approached life with as much intellectual rigor and discipline as he his writing had flourish.

His stepson Seamus Mahoney, a Minneapolis lawyer whose mother, Barbara Mahoney Brooks, began seeing John Brooks when Mahoney was 16 before marrying four years later, was impressed that Brooks managed a strict schedule every day: writing from breakfast ‘til noon, a cocktail and lunch, followed by an afternoon of reading.

“I suppose that’s what writers need to do, have the self-discipline,” he said.

He also recalls that Brooks was a man with an incredibly sharp wit.

“He did not suffer fools gladly, and he could be a little cranky as a person, but he was fun to have dinner with because he was very knowledgeable,” he said.

The dinners he shared with Brooks in his Barrow Street home in New York City were adult, intellectually stimulating affairs that were sometimes followed by friendly cigars and where talking points always had to be rock solid.

“If you said something that wasn’t well-grounded, he would call you on it, because he probably knew the facts,” said Mahoney.

Tragedy struck when Brooks suffered a stroke in his twilight years, which devastated his mind and relegated him to a nursing home. Mahoney recalls the bitter irony:

“All of a sudden, this guy I admired for his intelligence and his acumen,” he said. “To see him deflated, and lost, was a sort of strange feeling.”

“It was a tragic end to a bright life,” he continued. “He would have rather have died outright than to have lived for a few years and not use his brain.”

Melvin Backman, from North Charleston, S.C., is a senior journalism major at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He has interned with the finance team at Reuters and will be with the Wall Street Journal’s Money and Investing section this summer.