By Stacey Northup

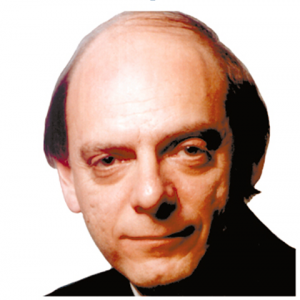

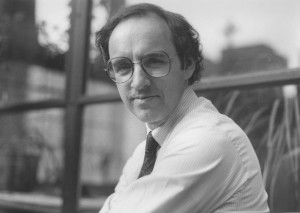

The memory of Gary Klott continues to have great influence on the Society of American Business Editors and Writers’ code of ethics. Throughout the ethically challenging times in the world of business journalism, Klott educated members and encouraged them to follow a strong code.

Klott was born on Oct. 4, 1949, in Albany Park, Ill., where he was raised. After graduating from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 1971 with a degree in economics, Klott served as a lieutenant in the Navy in Vietnam. Until 1974, he was a communications officer aboard the USS Kitty Hawk, according to his obituary in The New York Times.

Following his time in the Navy, Klott began his journalism career. He spent a little time as a television reporter at a small station in Nebraska but quickly moved on to start a small paper in Kankakee, Illinois. Then, he went to work at the Ft. Lauderdale Sun Sentinel and soon after, Klott became a tax reporter for The Times, covering tax law changes.

This was quickly followed by a position as a columnist for the newspaper writing the “Tax Watch” column. Klott then left his job at The Times to write three different syndicated personal finance and tax columns, including one syndicated by Tribune Media Services, in the late 1980s. He would write on tax laws, real estate and personal finance for these columns.

With such great knowledge on the topic of taxes, Klott founded the website TaxPlanet.com in 1999, offering information about personal taxes. The advice was read by both individuals and tax professionals. The website garnered dozens of national awards and Money magazine rated it one of the top 50 financial websites, according to Klott’s obituary in The Los Angeles Times.

Klott also authored three books. “The New York Times Complete Guide to the New Tax Law,” “The New York Times Complete Guide to Personal Investing” and “The Complete Financial Guide to the 1990s” all stemmed from his knowledge and expertise of taxes and personal finance.

“Gary was a very gifted writer,” said Randall D. Smith, former president of SABEW. “Not only a gifted writer, but he understood some of the most complex things and put them in the simplest terms. When you read his stories and columns, you understood what he was trying to get across.” In the February/March 2001 issue of The Business Journalist, Klott offered advice to other business journalists on how to cover taxes.

Klott was active in SABEW for many years, and aggressively championed elevated standards of ethical behavior, particularly serving as the president of SABEW in 1994-1995. “We don’t think about taxes or personal finance with Gary, but mostly ethics,” said Smith. “The reason why is because Gary led a lot of discussions. He kept us morally straight during a challenging time in the ’90s when there was a lot of money floating around and great temptation for business journalists.”

Klott’s wife, Sandra Duerr, executive editor of The San Luis Obispo Tribune, had similar thoughts: “Gary was best known for his coverage of tax issues, development of the critically acclaimed TaxPlanet.com and pushing SABEW to strengthen its ethics code in 1991 to address advertising encroachment to retain the integrity of business journalism.”

From 1991-1992, Klott chaired SABEW’s Futures Committee. A majority of this committee’s recommendations received unanimous support from the board at a November 1991 meeting.

Duerr said these recommendations included, “distinguished achievement awards (an annual writing contest and separate awards for lifetime achievement in business journalism); a 24-hour jobs hotline; an electronic bulletin board; a bi-monthly president’s newsletter; a stepped-up membership campaign; an outreach program for minority journalists; and a greater focus on ethics.”

On Aug. 10, 2002, Klott died of a massive heart attack in his home in San Luis Obispo. He was 52.

Due to Klott’s strong sense of ethics that guided every step of his career, Duerr, along with Klott’s brothers David and Richard Klott, created the Gary L. Klott Business Journalism Ethics Fund after his death. This fund is committed to championing the cause of ethics in business journalism.

“His influence broadened when he began working for The New York Times and continued on his own,” said Duerr, who was also a SABEW president. “That’s due not only to the depth and quality of his work nationwide on taxes and personal finance, but also his leadership with SABEW and the news industry on ethics.”

“Gary accomplished a great deal in his relatively short life,” said Duerr.

SABEW’s 11th business journalism ethics symposium held in Klott’s name will be held in 2013. The seminar focuses on topical, relevant issues every year and allows discussion for how people would response in various ethical situations.

Stacey Northup is a native of Raleigh, N.C. ,and a Journalism and Mass Communication major in the Class of 2013 at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.