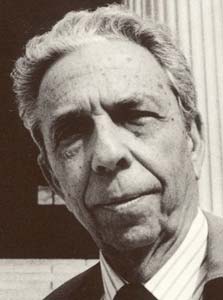

Hardly anyone in business journalism knew his name, but when he announced retirement, The Wall Street Journal’s managing editor pled, “But, but — we can’t do it without you.”

Dan Hinson remained invisible to most of The Journal’s news department and readership. During his 37 years with the paper, he never reported, never had a byline published or a big blockbuster story to puff up his ego.

But he liked it that way. It was part of his humility, said Judy Hinson, Dan Hinson’s wife of 55 years.

Dan Hinson’s behind-the-scenes role as a copy editor and later as an assisting managing editor for The Journal left a hidden imprint on one of the most widely read financial newspapers.

His core job as assistant managing editor was to get the newspaper out and serve as the key liaison between the advertising and news departments.

By the time of his retirement in 1997, The Journal had expanded from a one-section to a three-section newspaper with the establishment of European and Asian editions — expansions executed under the trudging, unseen work of the well-regarded editor.

Born in Yonkers, N.Y., Dan Hinson grew up in New Jersey towns. Dan Hinson’s father was a research analyst for one of the largest brokerage firms in New York, which sparked his interest in business.

Dan Hinson attended the University of Iowa, where he earned a degree in journalism and gained experience as the editor of his campus newspaper, propelling him in the direction of management from a young age.

“That’s where he really began his interest in that facet of the newspaper. He never had an interest in writing; he was always more interested in the managing aspect,” Judy Hinson said.

After one year of reporting for The Cedar Rapids Gazette, the only reporting job during his journalism career, he began his career at The Journal and held positions in news production in New York, Cleveland and White Oak, Md.

Dan Hinson and his wife moved back to New Jersey when he became a national news production manager in New York.

Equipped with sharp antennae for young talent, he recruited college journalists and was an avid recruiter of women to join the newsroom.

Dan Hinson died on Feb. 18, 2013, when he was 77 years old.

John Prestbo, former editor and executive director of Dow Jones Indexes, said Dan Hinson would primarily be remembered for his establishment of the European and Asian editions — for transforming an idea into a tangible thing.

“All that took a great deal of attention to detail, negotiating with people who had different agendas and making it work smoothly in the end,” Prestbo said.

At The Journal there was no link between the news and advertising departments with two exceptions. One was the publisher to whom both departments reported, and the other was Dan Hinson who worked closely with an advertising counterpart, Bob Higgins.

“It was a bit liking doing a daily jigsaw puzzle complicated by the fact that certain news columns had to run in certain places while certain ads required certain prepaid positions,” said Peter Kann, former CEO of Dow Jones & Co.

His ability to adapt to the fast-changing news environment was notable, said Jim Pensiero, a deputy managing editor for The Journal.

During his tenure at The Journal, Dan Hinson oversaw drastic changes in The Journal’s news production, which shifted from hot-metal composing to desktop publishing.

“He had to bridge those technologies,” Pensiero said. “He had to help us as a news organization. That’s always a battle — you can have the world’s greatest story, but if you don’t get it on a page, you don’t get it out.”

Prestbo said Dan Hinson took these technological changes in stride.

“I thought that for someone who was on the back half of his career, he was embracing of new things,” Prestbo said. “It all had to be integrated into this daily rush of stuff that all had to be settled into.”

Under the daily pressure of coordinating efforts between the advertising and news departments, Dan Hinson never lost his composure.

“He was always very nice, very accommodating, always pushing for that resolution,” Prestbo said. “I learned from Dan keep your cool. It may be urgent and important, and the clock may be ticking, but don’t lose your cool.”

But even though he was calm, cool and collected, Dan Hinson’s managerial duties necessitated bluntness at times.

“I wanted to get new dictionaries because ours were really out of date and beat,” Pensiero said.

“The guy who ran the numbers said, ‘we’re not going to do that.’ Dan chews this guy out and says, ‘what business do you think we’re in, buddy?’”

Dan Hinson was not afraid to confront coworkers when they violated his vision of collaboration at The Journal, Pensiero said.

“He would remind more egocentric people in the newsroom,” Pensiero said. “He would say, ‘you know what, you’re not as important as you think you are.’ And for some of those people, they really needed to hear that.

“I’ll tell you, Dan stood for something. He stood for The Wall Street Journal.”

Sarah Chaney is a native of Charlotte, N.C., and a business journalism and French major in the Class of 2016 at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.