By Andrew Willard

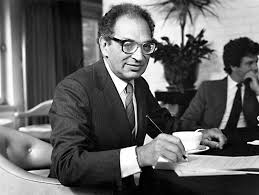

The business desk of The Dallas Morning News in 1980 was little more than a small classroom where Al Altwegg presided over his eight pupils.

As business editor, Altwegg taught the tools of the trade just before the beat came into vogue.

“Business news was where the paper stuck people that they didn’t know what to do with,” said Cheryl Hall, who Altwegg hired as an intern in the summer of 1972.

But Altwegg was not concerned with glamor; he preferred being an active participant in the Dallas economy.

In his unpublished autobiography, Altegg talks about how he felt when he was asked to be business editor – and the relief he would bring to his predecessor.

“I was interested in business and what was going on in the business world, whereas Hand was mainly interested in automobiles,” he said in the book.

Altwegg was born in a small town in Wisconsin, but because of his Swiss father, the Midwestern child was a world traveler by the time he was a teenager.

Altwegg was raised in Germany and Switzerland after his father was offered a position managing an evaporated milk plant in the area. He later attended an American High School in Paris.

Hall said Altegg was a conscientious objector during World War II – she said he didn’t like the idea of killing people he had grown up with. She believes his moralist attitude carried into his reporting, calling him a man of great ethics.

Altwegg graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in the spring of 1938, after studying what he called the essential curricula for any aspiring business man. After finishing his education, Altwegg took to the road, driving across Iowa in pursuit of a job.

He finally found employment at the Herald & Review in Decatur, Ill where he got his first experience in the field of reporting. But more important than a job, Altwegg found two people who changed his life: Martha Maloney and Dick Weicker.

With Weicker, Altwegg was able to buy the Arlington Journal, which he ultimately abandoned after it merged with another paper in 1956. With Maloney, Altwegg found a wife and a future mother who would go on to bear his two children, Chris and Libby Altwegg.

Three years after the Arlington Journal venture failed, Altwegg joined the business news staff of The Morning News; one year after joining he was asked to be the business editor.

Dennis Fulton, current business editor at The Morning News, started working at the paper in 1977, three years before Altwegg retired.

By that time, Altwegg had been the editor for almost 20 years, and Fulton said he had an apparent effect on economic development.

“He did help bring the community together, and I know he had a huge following among the business leaders,” he said.

Chris Altwegg said his father had such strong relationships with the business owners, that the family could always expect extra presents at Christmas time, even though Altwegg would give most of them away.

“He always felt that it was important that people appreciate the business economy in Dallas,” Chris Altwegg said.

“But at the same time, not kowtow like you see some cities and states do these days.”

And even more than the business leaders, Chris Altwegg said his father felt an obligation to nurture his reporters.

“I have often said that (The Dallas Morning News) in those days reminded me of an old Southern plantation, where once you were one of their slaves, they felt responsible for you for the rest of your life,” Altwegg said in his autobiography.

After Altwegg retired in 1980, his old stomping grounds reached new heights.

“He just missed the the big surge in business journalism,” Fulton said. “(Altwegg) would’ve loved to see that.”

Fulton said the size of the staff grew tremendously during the 1980s and then peaked in the 1990s before leveling out in the 2000s.

Altwegg suffered from a stroke in the early 1990s that left him unable to speak properly, but he was able to share what he was thinking about by pointing to the stories he had written in his autobiography.

Altwegg died on July 5, 2001 due to health issues brought on by his declining health.

Hall said Altwegg used to say that business news was as simple as finding out what people eat for dinner.

“Some eat steak some eat hamburger and some don’t eat very well at all,” she recalled.

“He showed me that business was a vibrant beat, and, in fact, you could make a business story out of anything.”

Andy Willard is a broadcast journalism major at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Class of 2015, and works for The Daily Tar Heel. He is a native of Jamestown, N.C.