By Callie Bost

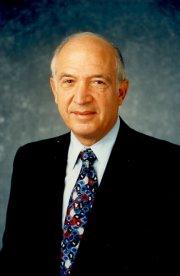

Dan Dorfman was one of the most influential business journalists and a proponent of get-rich-quick stock picking.

But Myron Kandel remembers “Danny” as the stout journalist who had a penchant for gourmet food, wine and Mickey Mouse neckties.

“He was a rather short guy with a squeaky voice, but he was a very determined reporter,” said Kandel, who worked with Dorfman at the New York Herald Tribune and CNN.

Dorfman, who was born in Brooklyn, N.Y., on Oct. 24, 1929, took a less traditional path than most in business journalism. Dorfman’s parents divorced when he was young, leaving him in a Brooklyn orphanage for two years. Dorfman never went to college. Instead, he attended the New York School of Printing, a vocational high school, before enlisting in the Army. Dorfman started his journalism career as a copyboy for Fairchild Publications, Kandel said.

“If anybody could be described as self-made, it was (Dorfman),” Kandel said. “He came from very humble beginnings.”

Dorfman was hired as a retail reporter on the garment industry for Women’s Wear Daily, a Fairchild publication. At that same time, Kandel was covering the retail beat for The New York Times. Kandel joined the Herald Tribune in 1964 as the financial editor. In 1965, Dorfman was the first journalist Kandel hired at the Herald Tribune.

While at the Herald Tribune, Kandel and Dorfman became great friends. Kandel discovered Dorfman’s knack for investigative reporting.

“Pound for pound, Danny was one of the best reporters I ever knew. He was insatiable in pursuing the story,” Kandel said.

One night while leaving the Herald Tribune’s newsroom, Myron Kandel noticed Dorfman on the phone at his desk. At the time, Dorfman was working on a story about American businessman Meshulam Riklis, but Riklis would not talk with Dorfman about his latest acquisition.

After exhausting all avenues of communication, Kandel said Dorfman decided to call Riklis’ wife.

“Dan said, ‘Mrs. Riklis, do you think it’s right that your husband won’t talk to me?’” Kandel recalled. “That was persistence – that was how hard-working Danny was.”

In the late 1960s, Dorfman moved to The Wall Street Journal to write “Heard on the Street,” a daily investing column. True to the column’s name, Dorfman would talk to Wall Street traders about what stocks could see movement that day and write a column based on these tips.

The “Heard on the Street” column was different from the investigative reporting that Dorfman did for Women’s Wear Daily and the Herald Tribune. Dorfman focused on more exclusive, breaking news for “Heard on the Street.”

Barney Calame was a reporter for The Journal in Washington while Dorfman was working at the paper’s New York City office.

“(The ‘Heard on the Street’ column) was very secretive,” Calame said. “The (WSJ) was very careful about limiting who knew what was running in the column in the next day.”

Eventually, Dorfman left The Journal for New York Magazine, where he returned to his investigative roots by writing “Bottom Line,” a column focusing on behind-the-scenes issues in business.

“After his Wall Street Journal days, there were other people who hired him and wanted him to be very explosive…I don’t think the (WSJ) wanted him to be far out or bold in his writing,” Calame said.

Following his time at New York Magazine, Dorfman wrote financial columns for Esquire, USA Today, The Daily News and later, Money magazine.

Dorfman found his way into broadcast business journalism when he became a regular contributing columnist for CNN’s business news in 1980. At the time, Kandel was the financial editor at CNN. Kandel said Dorfman engaged in casual, lively banter on air instead of sticking to formal broadcast norms.

“(Dorfman) was the closest thing to a Damon Runyon character that business journalism has ever had,” Kandel said, referring to the famous Broadway author from the early 1900s. “He was a refreshing face on television; he was not the kind of face or voice on national television that people expected. His boundless energy captivated many people.”

Dorfman’s most-famous broadcasting stint was in the early 1990s at CNBC, where he was featured in daily, three-minute segments with his stock buy-or-sell recommendation for investors. Dorfman gathered his stock tips from various Wall Street sources, but he never disclosed who these sources were.

Paul Steiger, executive chairman at ProPublica, worked as a reporter at the The Journal and later became its managing editor. Steiger and Dorfman never crossed paths at the paper, but Steiger said he was familiar with Dorfman’s ability to dramatically move the market with his reports.

“He was a phenomenon,” Steiger said. “He was a stock picker, not as an analyst, who could move markets.”

Dorfman’s effect on the market was so pervasive that in the mid-1990s, the Chicago Stock Exchange began halting activity on a stock that Dorfman recommended in the minutes after his report. NASDAQ proposed the same rule to the Securities and Exchange Commission in 1996.

In an April 1996 interview with the Seattle Times, Dorfman said he supported these rules.

“Anything that can make for more orderly markets makes sense,” Dorfman said to the Seattle Times.

According to The Times, Dorfman was earning almost $1 million annually from his gigs at CNBC and Money, making him one of the highest-paid business journalists of the 1990s.

Dorfman’s career hit a roadblock in 1995 when BusinessWeek magazine reported that the U.S. Attorney General was investigating Dorfman’s relationship with Donald Kessler, a public relations professional who was under investigation for insider trading. In 1996, in the middle of the federal investigation, Money fired Dorfman because he would not reveal his sources.

Dorfman said the allegations were unfounded in a 2008 interview with Chris Roush, a business journalism professor at UNC-Chapel Hill.

“(BusinessWeek) would never admit it, but that was a bogus story, and they now know it,” Dorfman said to Roush. “I told them I had never been contacted by the Justice Department. Thirteen years later, no one has ever contacted me from the Justice Department.”

Allan Sloan, a senior editor-at-large at Fortune, wrote a Newsweek column in 1995 addressing BusinessWeek’s accusations against Dorfman. In the column, Sloan dismissed the accusations as false but warned readers about Dorfman’s “quick hit” stock recommendations.

“Dan did things that were sloppy, but nobody ever charged it as illegal,” Sloan said in a phone interview.

Kessler ultimately pleaded guilty to securities fraud and tax evasion charges. Dorfman was never charged or convicted on any allegations.

In May 1996, Dorfman suffered a mild stroke that ended his broadcast career. After his stroke, Dorfman wrote for The New York Sun, Financial World magazine and various websites.

Dorfman died on June 16, 2012.

In his interview with Roush, Dorfman said that he did not want people to remember him for the money, fame or stock tips, but by his propensity to give back.

“On my tombstone, I would like it to read, “Here lies Dan Dorfman, a reporter who cared,’” Dorfman said. “All that I’ve tried to do is to give to the masses what was known to a chosen few.”

Sloan knows this side of Dorfman well. Sloan credits Dorfman for taking interest in him when Sloan was a young journalist living in Detroit in the 1970s – a period, Sloan said, “when people at The New York Times wouldn’t even return my phone calls or take me seriously.”

Sloan said he would occasionally travel east to New York to visit family. During one of these visits, Dorfman agreed to have lunch with Sloan and talk to him about Sloan’s budding journalism career. In the 1990s, Dorfman invited Sloan to join him at Money. Sloan declined and instead joined Newsweek.

“He was this enormous star, and I was nothing, and he went out of his way to be really nice to me,” Sloan said. “I try to do the same with people today.”

Callie Bost is a senior at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s School of Journalism and Mass Communication. She will intern this summer at Bloomberg News in New York.