By Madeline Will

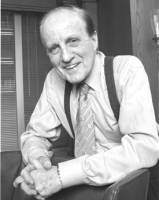

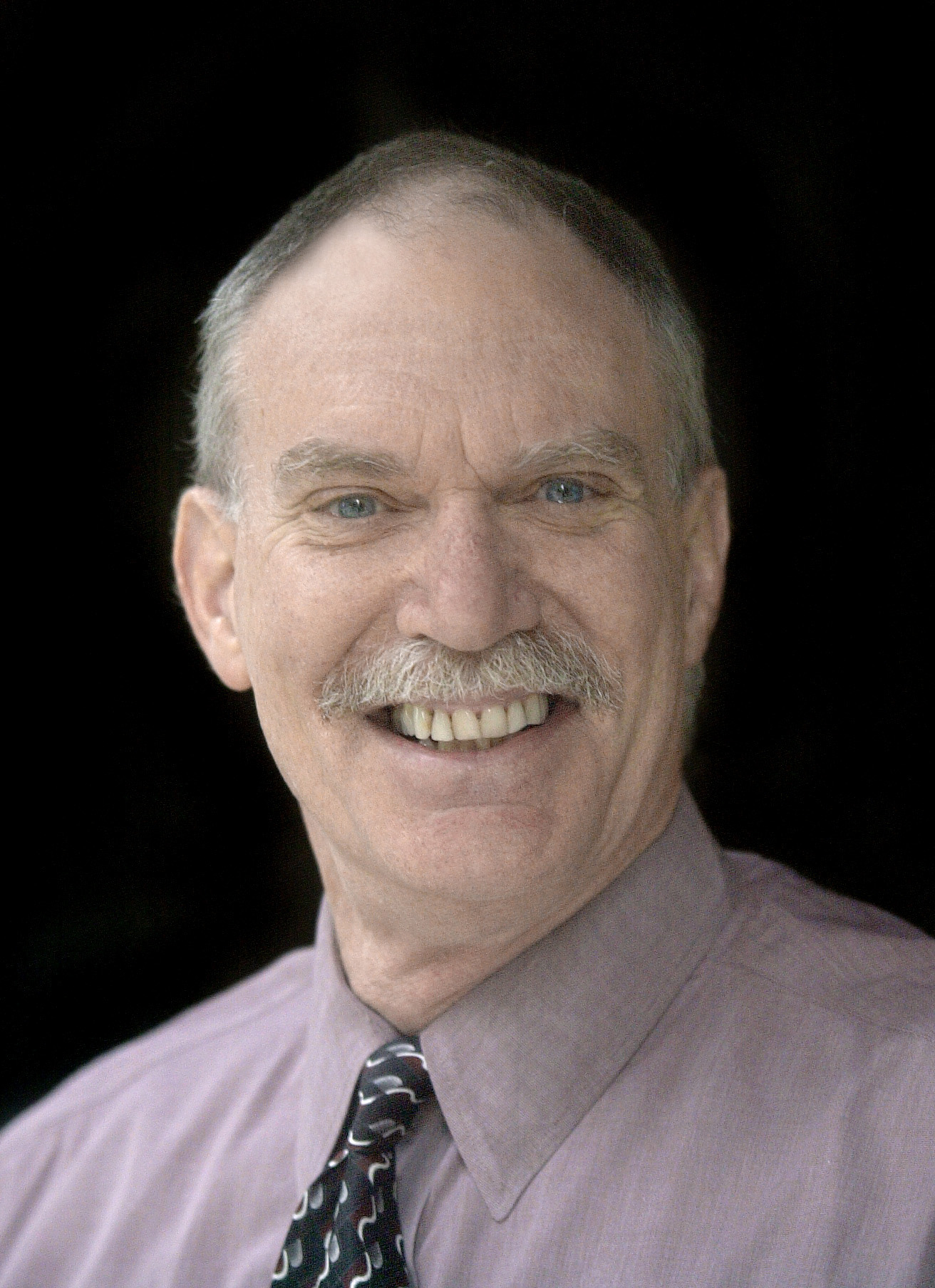

For more than half a century, Harlan Byrne was an icon of financial journalism.

To young reporters, he was a fountain of institutional knowledge and a reminder of a past era of journalists. He covered companies for about 60 years at both the Wall Street Journal and Barron’s, Dow Jones’ weekly investment magazine. He started working at the Journal in 1949 and later became assistant bureau chief in Chicago — the city that he stayed in for the rest of his career. He moved to Barron’s in 1985 and continued writing until 2006.

Byrne was an old-school newspaperman. He would wear a suit and tie to the office. He had served in World War II after college, and he was fond of martinis and White Russians. Former Barron’s colleague Richard Rescigno still remembers Byrne’s routine after filing a story: go downstairs to the building’s bar, drink a few martinis, and then go back upstairs to start a new story.

He was a reporter before the Internet, and the introduction of computers to the newsroom threw him for a loop, said Jon Laing, who worked with Byrne at Barron’s. Byrne kept hundreds of files on different companies — clippings from the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal and any information he had compiled in the course of his reporting.

Laing cleaned out Byrne’s office after his death.

“It was a two-day process,” he said. “I was filling dumpster after dumpster with the files.”

At the Journal, he supervised the training of new journalists, said Todd Fandell, who worked with Byrne for years at the Journal. Byrne taught reporters how to do their first stories.

Fandell, who later served as editor of the trade publication Advertising Age, said Byrne influenced his own career — “No question about it.”

“He just knew all the rules, you could always count on him for advice on how to go about getting stories,” Fandell said. “He just had the know-how.”

Byrne was a constant in Chicago’s business journalism scene, even as the financial landscape changed throughout the years. For decades, the city was a major banking center. It no longer is, but Chicago remains the hub of the commodity market.

Byrne covered many important industrial companies that were based in the Midwest, Rescigno said, going beyond the surface of the news to strike at the heart of the issue and analyze companies’ future prospects.

Many business journalists and editors are based in New York and don’t know much about the Midwest, Rescigno said. But Byrne, who graduated from the University of Missouri School of Journalism, was a master of the region.

Rescigno, who served in various editor positions, including managing editor, during Byrne’s time at Barron’s, said if he ever had a question while reading Byrne’s copy, he would call and ask — and Byrne always had the information in his notes.

“He was a bulldog in terms of getting stuff,” he said. “He was pretty resourceful.”

Byrne was nominated for several awards in the course of his career, including a Pulitzer Prize nod in 1982.

He was a journalist who simply loved to write, said Bob Goldsborough, who wrote Byrne’s obituary for the Chicago Tribune. Byrne used to tell people that he would keep writing until his stories stopped making sense.

Even after he had retired in 2001, there was still a desk for him at Barron’s. He continued writing and contributing until just a few years before his death. Byrne died on Feb. 23, 2010. He was 89.

In a column after Byrne died, his former colleague Alan Abelson — a Barron’s columnist and former editor who is now deceased — praised Byrne’s ability to cover the industrial companies of the Midwest.

“He was a meticulous reporter of the highest integrity, a prolific writer, an unflappable, low-key interviewer, no matter how grouchy and intimidating the subject, an astute judge of markets and possessed an extraordinary ability to separate fact from hyperbole, truth from spin,” Abelson wrote. “We can’t recall a single instance when one of the countless pieces he wrote elicited a complaint of inaccuracy from even the crankiest corporate chieftain.”

Byrne, who had a slight Missouri accent, was personable and easy to get along with — “an aw-shucks Midwestern type” — and that helped him when dealing with difficult sources, Rescigno said. That also endeared him to his colleagues.

“He was always even-tempered, he never seemed to have down periods,” Fandell said. “He always was in good spirits and very encouraging to other people.”

Byrne kept in touch with many of his former colleagues — Fandell said Byrne never forgot anyone. The two of them would meet for lunch every so often.

“He knew just about everything about business journalism,” he said.

Madeline Will is a native of Charlotte, N.C., and a journalism major in the Class of 2014 at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.