By Caroline Schaberg

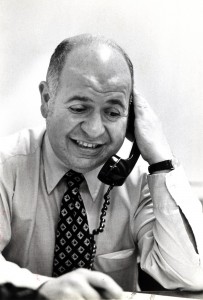

When Leonard Silk began his career as a journalist post-World War II, most business publications simply provided their readers with economic data and statistics. The information was neither newsworthy nor particularly interesting to read.

Silk changed all of that by bringing more of a personal approach to coverage of the economy. He wrote in layman’s terms so that his readers could more easily understand news from the business world.

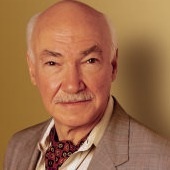

“He came into the profession as an enterprise in educating and enlightening the business class in the post-depression period when they were at least somewhat persuadable,” said his son Mark Silk, director for Study of Religion in Public Life at Trinity College. “He really focused on economics as it had emerged after the war and brought economic awareness to his readers.”

Silk was born in Philadelphia on May 15, 1918. He began his career as a reporter while in college at Wisconsin, where he edited Octopus, a humor magazine. It was here that he encountered professors who argued that economists should focus not only on the big picture, but also on the effects of the markets on individuals.

From there, in 1940, Silk continued to Duke University to earn a Ph.D. in economics, a rare feat for a journalist at the time. Following the war, Silk used this degree to become an economist for the United States Mission to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

It was after this stint that Elliott Bell, Business Week’s new editor, hired Silk to head the economics section of the publication. Silk worked here from 1954 to 1969 and preferred to hire journalists who, like himself, had a background in economics.

“He was brought into Business Week with the idea that businessmen needed to be brought up to speed on the Keynesian revolution, and that if they simply subsisted on The Wall Street Journal, they wouldn’t know what they needed to know to get along in a new economy,” said Mark Silk.

A year after leaving Business Week, Leonard Silk went to work for The New York Times as a writer of economic columns and editorials. He worked there until retiring in 1992.

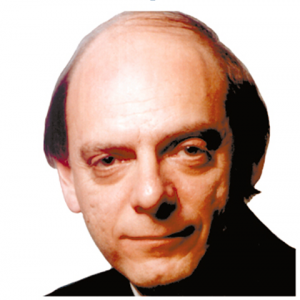

“If he had a striking bias, it was bias toward news,” said David Warsh, a journalist and author who has covered economics for the Wall Street Journal and other publications since the 1970s. “He just knew how to get a lot of people into the paper. He really set the standard, and until he stopped, there was no one better.”

One way that Silk got people into the paper was by profiling economists themselves.

“Silk’s profiles fit the age,” said Tiago Mata, a journalist and writer who has researched and written on Silk. “Post-Sputnik America saw a public affirmation of knowledge and knowledge producers. There were whiz-kids at the Pentagon and the White House. Claims about America’s congenital anti-intellectualism seemed not to apply any more. It was appropriate that Silk report on economists who were growing in their influence of public affairs. It was felicitous that there was an interest to learn more about them. Silk happened to have the right training, contacts and disposition to do the job.”

Silk also managed to find time to author a book, “The American Establishment,” which he co-wrote with his son Mark. It was published in 1980.

“The idea to write a book came before we actually had a topic in mind,” said Mark Silk. “He did have personal connections to a bunch of the institutions that we wrote about, so that’s how it ended up coming together.”

Leonard Silk also penned a variety of other books, including “Nixonomics,” “Making Capitalism Work,” and “Economics in Plain English.”

“I did not want to write down to people,” The Times quoted Silk shortly before his death. “I wanted to make economics accessible. I thought any idea could be plainly stated.”

Silk died in 1995 at the age of 76.

Caroline Schaberg is a native of St. Louis, Mo., and a senior business journalism major in the Class of 2013 at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She interned for Bloomberg News in New York City last spring.